Adjunct Professor Mark Gallimore has developed a history lesson or module focused on the experiences of women, people of color, and LGBTQ Americans during World War II. Built for a U.S. military history course, it aims to introduce mostly freshmen or non-history major upperclassmen to an important element in U.S. military formation: discriminatory rules imposed by the U.S. government on who can serve in the armed forces, and in what capacity, and challenges to those rules. As a force majeure World War II compelled practical and eventual official changes to U.S. military policy, and this history is a vehicle for students to explore the social, cultural, and political implications in the context of Canisius’ Jesuit, Catholic social, intellectual and spiritual traditions.

Dr. Gallimore initially developed versions of this module for his HIS201: United States Military History and HIS124: U.S. History since 1877 courses, offered by the Canisius College history department. In the military history course, students encountered it after having worked through modules similarly focused on the relationship between military power, institutions, and broader civilian contexts. Students also studied more traditional military history: tactics, technology, strategy, the constitution of military forces, and course of battles, campaigns, and wars. More broadly, Professor Gallimore imagines several goals for the World War II: Diverse Experiences module:

- Integrate various principles or tenets of Catholic Social Teaching, the Catholic Intellectual Tradition, and Ignatian Pedagogy and Jesuit Spirituality into a liberal arts or social sciences course.

- Develop an expansible lesson that can serve as a larger or smaller part of a course, depending on what other elements, content, activities, learning goals or objectives may also be in that course.

- Develop course activities or assignments that range from proven and traditional pedagogy, to newer methods that take advantage of information technology.

- Use “off-the-shelf” course content, available to students through the Bouwhuis Library at Canisius College, or content purpose-built by the instructor to efficiently promote discussion and reflection on a topic by undergraduate students in various majors.

- Serve History Department Goals and Objectives, specifically Objective B and C of goal 1, and all three objectives of Goal 2. However this lesson can be adapted to many departmental, program, and Institutional Goals.

Here, you will find:

- Examples of how traditional teaching techniques, combined with a curated blend of sources and media types, can be built into a lesson focused on concerns central to Jesuit mission and identity.

- Resources you can use to build a similar lesson, according to various formats, serving similar learning objectives tied to Ignatian Pedagogy, Catholic Social Teaching and Intellectual Traditions.

- Links to tutorials and other guides for web-enhanced teaching and learning.

Military History as a Site and Situation for Catholic, Jesuit Mission and Identity?

Studying wartime activities may seem incongruous with Catholic Intellectual Tradition and Social Teaching, as well as Jesuit Pedagogy. But there are compelling reasons to do so.

Method

In this lesson, Professor Gallimore has students read, watch, and listen to sources which discuss several different perspectives of men and women in the United States armed forces during World War II. Some of these sources are work by historians. Others are primary sources, or those written or recorded by veterans of the war. In an interactive online lesson, students engage with a blend of media that present several different but related topics. While this includes text, it also features several “lean-forward” features such as short sound clips and image galleries that prompt student interaction, rather than just consumption of the content.

Depending on how the module is employed, in several exercises students reflect and respond to the sources. For example, this module might include simple and highly traditional exercises: a reading comprehension quiz or short essay responses to reading questions. Or, students might engage in several classroom or online discussions, produce audio or video reflections, or follow up with mini-research projects of their own concerning the intersection of racism, sexism, and discrimination against LGBTQ citizens in American life and culture with World War II service.

Options

There are several possible variations on this lesson. One is as an online lesson, either within an online or hybrid course, or as a single week’s replacement for classroom lessons. Alternatively, the content and activities can be selected for use in support of classroom discussion or other activities, perhaps over a 2-3 week period. The lesson can be narrowed by leaving out some content, or operated in tandem with a student research project, for example focused on diversity, equity and inclusion, within military service in a historical context.

While constructed for a U.S. military history course, variations on this lesson might be employed in a variety of humanities, liberal arts, and social science courses aimed particularly at freshmen, non-majors, and core curriculum participation.

Each of the sources outlined below may be used in any combination, and to greater or lesser degrees. For example, both the Bérubé and Fessler volumes can each be assigned in their entirety; both are useful for undergraduate studies. Or, as Dr. Gallimore has done, portions can be assigned so as to provide greater breadth in an intersectional lesson.

Similarly, student assignments can range from a few quizzes (low time and effort for professor and students) to follow-on research projects that encourage students to explore different aspects of the topic. These can be individual research papers, or group efforts to create resources such as interactive lessons, wikis, or videos, as modeled by the Gallimore’s interactive content.

In any combination these sources should provide excellent opportunities for student discussion, be it online or face to face, synchronous or asynchronous, or in groups of various size.

Content

For this lesson, Dr. Gallimore draws from a blend of sources to develop a content set. Each source is comparable with others so students can understand how historical questions bearing on one social group’s experience might inform study of another set of circumstances experienced by those of a different racial or gender identity.

We can cultivate empathy, leading to solidarity, when we read and hear about the experiences of those in past, especially in traumatic situations. Specific to this lesson students evaluate policies and their consequences (intended or otherwise), concerning public service, developed in a reputedly democratic framework. How do public policies promote, respect, deny or dismiss the rights of others, especially in the context of their public service? How are prejudices installed into public institutions and policies, and how might they be undermined by a combination of extraordinary circumstances and savvy strategies of those oppressed? Soldiers and sailors are workers, and the conditions of their service are measures of respect (or lack thereof) of their rights and contributions. Various scholars, activists, and journalists have described the connections between prejudice, poverty, economic and social precariousness, and vulnerability, and this bears upon the circumstances of military service. Japanese-American service personnel often left behind family incarcerated by the federal government in concentration camps. These people were also practically poor, having lost property – the fruits of their labor – when their rights as citizens and humans were stripped away in 1942.

Comradely love is ubiquitous in social studies of war, and many veterans who faced real prejudice throughout their lives comment that in combat, survival compels a peculiar tolerance, or suppression of prejudice, among those wearing the same uniform. Exploring this phenomenon offers us insight into cultivation of anti-prejudice practices and habits of mind. At the same time, many women, African-American, Japanese-American, gay, and lesbian troops came to develop a sense of self-worth, citizenship, and solidarity because they worked, fought, sacrificed, and accomplished extraordinary feats in teams and units with those of similar racial, gender, or sexual identities.

Catholic Intellectual Tradition (CIT)

- Dignity of the Human Person

Catholic Social Teaching

- Life and Dignity of the Human Person

- A Call to Family, Community, and Participation

- Rights and Responsibilities

- Dignity of Work and Rights of Workers

- Solidarity

Ignatian Pedagogy

- The Examen

- Context

- Reflection

Sources

Note that for links to Bouwhuis Library below, you may need to be logged into the library’s website within your browser.

Allan Bérubé’s classic study, Coming Out Under Fire: the History of Gay Men and Women in World War II, is excellent for undergraduate students. This work discusses the experience of LGBTQ servicepersons during the war, particular in military service overseas. Bérubé makes several important arguments concerning LGBTQ service during the war, and it’s implications for LGBTQ solidarity and activism afterwards.

Professor Gallimore has students read Chapter 7. Officially, the U.S. military prohibited gay and lesbian Americans from serving, but students read how this policy was complicated and in some respects dislocated by the practical realities of widespread military service in a global conflict.

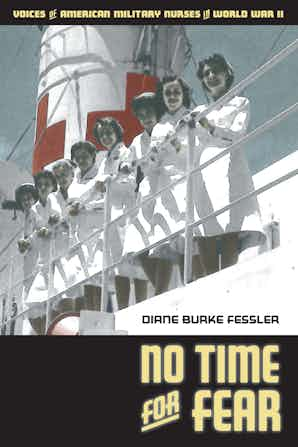

In her book No Time for Fear, historian Diane Fessler compiled various primary source accounts by veteran women Army and Navy nurses that discuss many aspects of their service during the war. Dr. Gallimore selected several accounts focused in the Pacific Theater of Operations that compare well with Eugene Sledge’s Marine memoir, and sources he developed concerning segregated African-American and Japanese-American units. But the Fessler volume can provide an excellent selection of excerpts useful for various approaches, and the entire book might be a good choice as a course text as well.

In a short video by the New York Historical Society, Columbia University Historian George Chauncey briefly describes “Soldier Shows” which, as government-approved activities, exhibited gender and even sexuality in ways remarkably diverse from culturally prescribed norms of the 1940s.

For undergraduate students raised on a common set of tropes concerning World War II, this is an extraordinary take. But it also connects with more traditional military history, such as the role of morale in sustaining field forces.

Professor Gallimore chose these sources based on several criteria:

- Each contained a perspective or discussion of one or more aspects of World War II service by those other than white, male, heterosexual Americans, complete enough so students could reflect upon and compare a source with others.

- Bérubé’s and Chauncey’s sources present scholarly arguments with skillful use of evidence, but are accessible to non-specialists and students whose reading comprehension skills are in development, rather than advanced.

- The accounts written by nurses were short enough to present diverse experiences in a relatively short block of text, that complimented the contextual source I built in the interactive lesson.

In Dr. Gallimore’s HIS201 course this lesson integrates with several others that shape classroom discussion and student assignment prompts. In other courses or disciplines, the lesson can compliment a diverse array of others, but for example, in HIS201:

- Students encounter racial and gender identities and policies earlier in the course, in discussing camp followers, the formation of segregated units, and the military dimensions of the invasion of the American West.

- Students read Eugene B. Sledge’s memoir With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa.

- Professor Gallimore delivers a short lecture that establishes the context of Japanese-American incarceration in World War II, and the campaign experiences of several black and Nisei units in Europe.

Custom Online Interactive Lesson

Instructors occasionally need to develop instructional content where and when content appropriate for their students is not available or practical. There are now many sources available for studying the various experiences of World War II veterans, but these can be cumbersome or expensive for an undergraduate course where this module fits alongside others focused on different learning goals. In this case, Dr. Gallimore created an online interactive lesson that provides context, comparison and intersection with other sources in the module. It includes a variety of different forms of complimentary media. The content concerning women works closely with the primary source excerpts in Fessler, and includes primary source images suitable for discuss in the classroom or online.

Video Mini-Lecture

As part of the online interactive lesson above, Professor Gallimore created a mini video lecture concerning black and Japanese-American army units, and specifically the relationship between (often white) leadership and the troops. Videos such as this can also be a standalone resource useful in other classes or shorter variations on this module.

Student Response

After students read, watch, and listen in the content set, they may respond in various ways, depending on the scale of the lesson.

Traditional assignments or activities, such as classroom discussion, quizzes, and reading response writing can be highly effective and relatively easy to implement.

Newer forms of activities, such as collaborative annotation or asynchronous discussions may require faculty to become familiar with some technologies, but can still have relatively high impact, become especially effective as prompts and rubrics are fine-tuned, and ultimately promote more student-student interaction, either for its own sake or as a preamble to a classroom discussion.

Assessments should effectively display student engagement with the sources and reflection on the learning goals and objectives that align with the mission and identity principles.

Teaching Presence: the professor should provide some written feedback on student writing, and actively engage in online discussion (without dominating any discussion topic.)

Social Presence: classroom discussion, online asynchronous discussions, and collaborative annotation feature student-student interaction, which can help students reflect beneficially on the sources and issues.

Catholic Intellectual Tradition (CIT)

- Dignity of the Human Person

- Innovation for the Common Good

Catholic Social Teaching

- Life and Dignity of the Human Person

- Call to Family, Community, and Participation

- Rights and Responsibilities

- Option for the Poor and Vulnerable

- Dignity of Work and Rights of Workers

- Solidarity

Ignatian Pedagogy

- Magis

- Women and Men For and With Others

- The Examen

- Context

- Experience

- Reflection

- Actions

- Evaulation

- Walking with the Excluded

Traditional Methods

The simplest of assignments or activities can be highly traditional, such as online or classroom quizzes, writing assignments, or different modes of classroom discussion. These are not flashy or particularly innovative but they are effective. Instructors may develop particularly effective prompts, rubrics, and even ways to measure student submissions against learning outcomes to assess effectiveness. Professors should not feel compelled to adopt newer or more complicated methods simply for the sake of innovation.

Quizzes and Surveys

A short quiz, perhaps delivered via the internet (D2L’s on-board quiz tool) and consisting of self-grading multiple-choice questions, can act as a worksheet to help students gauge their own comprehension of the lesson content. Delivered prior to the content or as a survey, students can reflect and record their own prior knowledge of the topic, perhaps for anonymous reporting in a subsequent class discussion.

While obviously quizzes or surveys with multiple-choice questions are of limited value, they are also low-stakes and low-effort for both instructor and student.

Writing

Writing response prompts can ask students to record their reflections on the lesson content, compare sources with one another, and even compare this lesson’s content with previous lessons in the course. For example, Professor Gallimore asks students to consider how the experiences of women, African-Americans, Japanese-Americans, and LGBTQ servicepersons compare with a more traditional war memoir by a combat Marine, Eugene Sledge, that students read prior to this lesson. An instructor might also ask students to unpack arguments made in the sources, to gauge their own understanding. In the second example below, Gallimore asks them to analyze Alan Berube’s complex explanation of an essential paradox in LGBTQ service during World War II:

In developing prompts, work back from the three traditions as learning objectives, in framing analysis. For example, the first question above asks students to consider the ways in which service personnel of various identities experienced similar things. Making such comparisons helps students develop several habits of mind: empathy for those in the past, and those in the future that may have relatable struggles that are obscured by social conditions. These support several of the core principles outlined in Catholic Social Teaching and Catholic Intellectual Tradition.

In the second question above, students are prompted to explore how wartime conditions exposed for many soldiers and sailors the dangerous absurdity of the military’s prejudicial policies. In reflecting on this paradox of LGBTQ service in World War II, students develop understanding of how prejudice can perpetuate in policy; “Our goal is thoroughly to understand the economic, political and social processes that generate great injustices,” according to the Apostolic Preferences. Students can also discover how prejudice and prejudicial policies can be disrupted.

Additional example prompts include:

- Identify contrasts among the varied experiences discussed in the sources. In what ways might one group faced a different set of realities, due to different mechanics within widespread social prejudices, than another?

- How might the War and Navy Department’s policies run into similar difficulties with regard to women, African-American, and Japanese-American service personnel, as they did with gay and lesbian troops?

- Japanese-American incarceration within the United States began in 1942, in the wake of U.S. entry into World War II. Segregation as a set of legal structures and cultural expectations aimed at African Americans existed for decades prior to that, and drew from precedents from slavery a century earlier. But can you describe ways that African-American and Japanese-American troops had similar experiences to Army segregation, and may have formed similar responses?

The methods outlined above are simple, mostly traditional, and in most respects common in history courses at many colleges and universities. But this demonstrates how tried-and-true methods familiar to faculty in various fields can bring elements of Canisius’ Jesuit mission and identity into lower-level and Core Curriculum classes that typical include students with many majors.

Web Resource Creation

Having students use audio or video tools or website development toolsets, professors can have students develop learning resources similar to those in this module. For example, students might record a five-minute videos about the topic of segregation in allied forces in World War II. Or, they may develop online interactive lessons concerning the role of prejudice and discrimination in U.S. military policy in other conflicts, or even in peacetime. Listed below are some easy-to-use tools for this kind of creation.

Student Interaction

Classroom conversation is a way to foster student-student interaction, which is accepted in various disciplines as a highly effective learning activity. This can be led or moderated by the instructor, or (in classes with perhaps advanced students) led by students as assigned by the instructor. Again, this is not new to instructors in various disciplines across campus. A variation on this is to have students discuss a prompt or series of prompt questions in smaller groups, before coming together as an entire class to present some insights or outcomes from the small group discussions. This can encourage students to be prepared and contribute in classroom discussions. It can also provoke and better organize more reflections or reactions to the sources.

Outside the classroom, asynchronous online discussions often take place according to a simple post-and-reply two-step process, but the COLI Guide to Teaching Online discusses various alternative formats.

Collaborative Annotation allows students to discuss a source in marginalia overlayed atop a web-based text source. This can encourage students to cite specific passages in conversation. Built into D2L, Hypothes.is provides this capability with Google Drive-based PDFs as well as other websites.

COLI has a basic tutorial for Hypothes.is that you can supply to your students. But this also demonstrates basically how Hypothes.is works, and why it is helpful for fostering student conversation.

Tools

Whether creating customized content for students, or having students create interactive content as an assignment, there are several options that require relatively low effort to learn.

D2L

There are simple tools built into D2L that are in most cases the easiest options for faculty. For example, D2L can collect and you can grade and provide feedback on student assignments using a Dropbox. You can build auto-graded quizzes for simple critical reading quiz or worksheet. Students and Faculty find D2L the most accessible asynchronous discussions toolset, although Hypothes.is, built in to D2L, is quite easy for collaborative annotation.

Website and Interactive Web Page Builders

Below are two internet building toolsets that are ideal for building online interactive lessons. Dr. Gallimore used Google Sites for the lesson linked above, but he has also used Sway for other lessons, and it is equally appropriate.

Google Sites is an easy-to-use, versatile website builder that can be great for producing multi-page online interactive lessons.

Microsoft Sway offers a powerful toolset to create online interactive lessons in a single, scrollable path.

Videomaking

Panopto allows faculty to create, manage, and embed video into their D2L course spaces. It is an all-in-one video platform that includes a recorder, basic editor, and additional tools to understand how students watch video.

YouTube can be helpful in certain circumstances where hosting video in Panopto is not appropriate. For example, if a professor wants to make a video that is both for her classes, as well as viewers outside Canisius College, YouTube is a good choice. Also, YouTube has an enormous array of third-party video content, including from leading academic, scientific or educational institutions.

Outside Panopto’s onboard recorders, there is a broad range of free tools for videomaking. These might include screencasting (such as Mac’s Quicktime, or PowerPoint’s video Export capability), or the use of webcams and phone cameras. You can use Panopto’s video assignment feature to collect video student assignment submissions, or can direct them to host video somewhere else, if the goal is to make it available to the public.